FAQ

Please note these FAQs were published and correct as of May 2020. We will update them periodically. If you have any questions to add please email us here.

How do the family feel about the film?

It’s best to hear from Dujuan and the family themselves – you can see their comments at the Sydney Film Festival HERE

DUJUAN: It’s both nice and a bit scary having a film about me. It’s nice because it’s the first time that I am releasing my story to the whole wide world. It’s scary because strangers are looking at my story. But I am proud that my story might give other Aboriginal kids hope and strength.

MEGAN (mother): We all want to give our kids a good future. But it’s hard to be a parent. It’s even harder to be an Aboriginal mum when everyone tells you you’re not good enough. I hear those people in newspapers, on tv and all over Alice Springs every day. I want you all to know that we, Aboriginal parents do love and care about our kids. I’m proud of this film because I think it sends that message to Australia.

CAROL (grandmother): The film is important to me because we want to show the world how our young kids are mistreated around Australia and around the world. It’s not fair – European people and First Nations people should be treated equally. It shows the world that our culture and language is still strong. It shows that we need to be honest about our past, that Australia was not ‘terra nullius’ to build a fair and just future.

We are sending a message to Australia about how hard it is for our kids in central Australia as well as in other states. The curriculum is written the way white people want to teach our children and there is so little about who they as Aboriginal people.

What changes does the film team want to see in Australia?

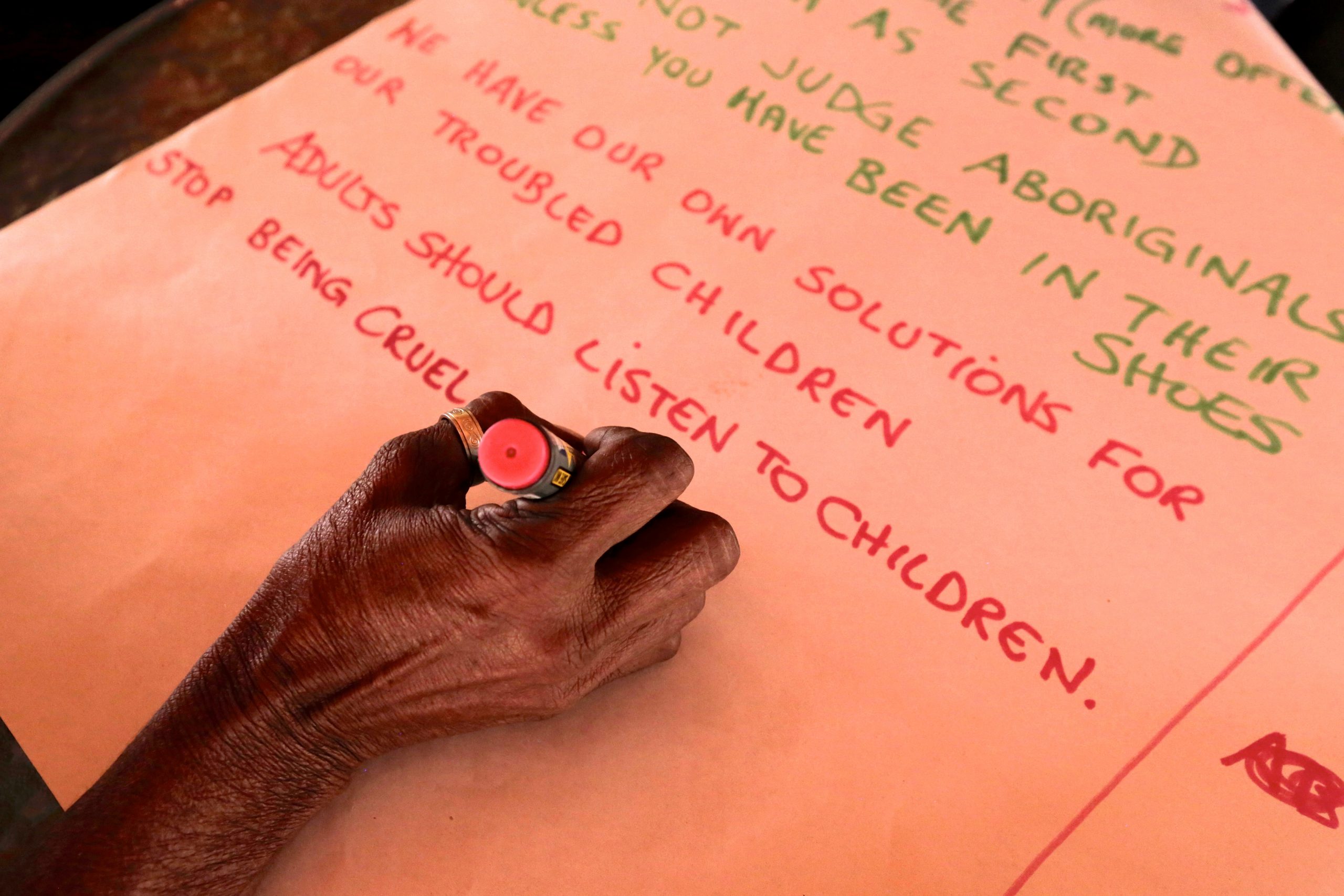

We hope that it stirs in the viewer a desire to help enact change, to understand a bit more about the experiences of First Nations children and communities – not only the challenges and trauma they too often carry but their strengths, their inherent wisdom. We hope that as Dujuan’s Mum Megan says, people see that Aboriginal parents love and care for their children. We hope that it inspires audiences to stand behind First Nations communities and back their solutions for change and equity because ultimately they are the only ones who know truly what’s best and what’s needed. Sustainable change will only be successful if it is indeed driven by the communities themselves, but they need us to back them, with our power and our privilege.

We hope that if audiences are moved by the incredible courage of this young boy that they are moved to find out more about Dujuan and his community work and calls to action. Which people can do at www.inmyblooditruns.com/takeaction. Here you’ll be able to connect directly with our key partner organisations and learn more about the goals of the community behind this film. Change happens first inside each of us individually, then collectively movements grow.

JIM JIM: All the families came together and agreed on what we wanted changed for our children. All the solutions for our kids come from empowering our people to be in control of their own lives. Right now, it’s not like this in Australia. We agree with Dujuan. We want to run our own schools in our own languages. We want our kids to know their history, their language, their culture and to know who they are and where they came from. We know they need a western education as well. But we all need to come together as one. Right now, our kids only get a western education. In other countries, Indigenous children can be taught in their own language at school. Our children should have this right too.

MARGARET (grandmother): We also want juvenile detention changed. In the Northern Territory, 100 percent of kids in juvenile are Aboriginal. This is so sad and not right.

No child should be locked up at all. But as a first step, we need to change the age of criminal responsibility from 10yrs to 14 years.

Going to jail as a child trains them to be ready for the big jail. We want the right to look after our kids when they muck up in town. They need to be grounded in culture out bush with family. We need to help them not harm them. We think that running our own schools is a way to stop kids getting in trouble. My grandson’s story shows how it’s all connected. The problems our children are facing are all in the film, but so are the solutions.

Where can I watch Dujuan’s speech to the United Nations?

In September 2019 Dujuan became the youngest person ever to address the Human Rights Council and the United Nations. He said “The Australian government is not listening so we came here to speak with you. Adults never listen to kids like me, but we have important things to say. I want my school to be run by Aboriginal people. I want adults to stop cruelling Aboriginal kids in jail. I want my future to be on land with strong language and culture.”

You can watch and read Dujuan’s full speech to the UN from September 2019 here.

We also made a short clip about his trip to Geneva here.

Where else has Dujuan spoken?

In August 2019 we screened In My Blood It Runs in the NT Parliament. The same day MP Chansey Paech read a speech from Dujuan on the floor of NT Parliament;

In February 2020 we screened the film at Parliament House, Canberra and another speech read by Senator Malarndirri McCarthy in the Australian Federal Parliament.

Why is the film called ‘In My Blood It Runs’? How is this connected to historical acceptance?

The film’s title, In My Blood It Runs, is Dujuan’s own quote and points to the intergenerational and embodied impacts of history – both positive and negative. “The first ones that had the magic was the First People, that had the Land. History runs straight into all the Aboriginals. It travels all the way through from my blood pipes all the way to the brain,”

Dujuan explains. Later in the film, Dujuan’s Uncle says, “It’s a hard world and it can easily drag you away from your culture. You have to learn about the past so it can help you for the future.”

Historical acceptance is about the need for all Australians to understand and accept the colonial wrongs of the past and the ongoing, intergenerational effects this history has on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Only through understanding and acknowledging past wrongs can Australia make appropriate amends and ensure that these wrongs are never repeated.

Typically, the truths of our nation’s history since colonisation have either not been taught in schools and universities or have been taught in ways that marginalise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices and perspectives. For this reason, we all to recognise that what we have learned about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, histories and cultures will be inaccurate or incomplete. Dujuan’s story demonstrates the importance of all of us, and especially teachers committing to an ongoing practice of challenging long-held assumptions by ‘unlearning’ and ‘relearning’ the history they have been taught.

What is the model of working and consultation behind this film?

Visit https://inmyblooditruns.com/about/#themaking

Is the model of consultation and collaboration new or unique?

We often get asked this question and applauded for taking a “unique” or “special” approach to collaboration, and at times we even fall into the trap of describing our work in that way too. The fact is that respectful collaborations are not the norm in Australian documentary especially when it comes to Indigenous stories told by non Indigenous directors & teams and so in some ways we do stand out. But it’s sad that we do – and without undermining the work, which we are proud of, we shouldn’t. This is how collaboration in documentary should be – working respectfully with our subjects shouldn’t score us points as filmmakers.

The other critical issue with the industry singing our praises as if we are creating a new path is that this erases the First Nations filmmakers & film industry leaders who have fought incredibly hard – and continue to fight – to have these principles respected by filmmakers. This deep work is evidenced in the Principles & Protocols document produced by Screen Australia and by the amazing First Nations screen industry itself. So yes let’s celebrate a film well made in partnership with its subjects – but lets look deeper to how the industry needs to step up – and take that lead from the First Nations people who have been telling these stories; both on screen & behind the scenes – for a long time.

It’s hard to watch the scenes in schools. Are those scenes real? Why did you include those scenes?

We like to sincerely thank the teachers and executive staff who participated in this film and enabled this story to be told. In doing so we hope that audiences recognize that the issues raised by this film regarding the education of First Nations students should not be laid at the feet of any one teacher or school; rather the responsibility should rest with the educational system from policy, leadership, teacher training programs and untimely seen through structural lenses. While it is our individual responsibility to take action for change, this change must be supported and resourced by the structures that govern our societies, in this case, our education system.

After sitting with Dujuan and his families and working with First Nations education partners over many years, we believe the education system should better equip and train teachers, from university onwards, to make their practice and classrooms culturally safe for all students. Teachers hold a powerful responsibility for the education of our children. They are increasingly required to carry a heavy load. We recognize that all teachers have their students best interest at heart and want to acknowledge the utter dedication and good work of schools and teachers across Australia, including those that feature in the film, to support First Nations students in their education.

Through the courage of Dujuan and his family we have been allowed, in this film, to see through a First Nations child’s perspective – a perspective we rarely have the opportunity to understand – showing us what it can be like to be an Aboriginal child experiencing mainstream schooling today. We believe that one of the ways in which this film is valuable is how it reveals this hidden child’s point of view.

These scenes are not fabricated. Our film team reflected over many hours about if and how to include the scenes we happened to capture of teachers delivering lessons in the classroom. We consulted the Arrernte families, Elders, advisors, mainstream educators and other organisational partners who guided the final decisions. After much deliberation, we included these scenes as our research indicated that these types of curriculum and classroom incidents are not one-offs, but are both historically and currently representative of some teaching practice in schools. We wanted to shine a light on the change needed at a systemic level to honour, value and support First Nations children’s identities in all areas of their growing and learning.

What is a First Nations led Education System and why do we need one in Australia?

This is one of the impact goals demanded by the families in In My Blood It Runs. A First Nations led education system would recognise the oldest Education systems in the world that continue today in First Nations communities. It would see the design of a world-class education approach that privileges language, culture and identity owned and delivered by First Nations people for First Nations children. This system would acknowledge the diversity of First Nations across Australia, maintaining key principles and visions, while creating space for locally-led approaches to education that respect the integrity of varying knowledge systems, country, culture and law. This system will recognise that First Nations people want their children to learn not only in their first culture and language but to have the full advantages of also learning global languages and knowledge. This system is based on the ability and strength of children and communities.

Currently there is no place in this country where First Nations children can walk into a classroom that privileges their language and culture. Australia has spent 240 years denying First Nations people this basic human right. As we see in the film, First Nations children are sent into culturally unsafe and damaging educational environments. These environments do not reflect their identity, language, family or knowledge-systems and often they deny and diminish the culture and identity of children. Too often children feel like failures and too many drop out of school. In Australia, First Nations children are subject to deficit and remedial approaches in education. Their ability as learners is not respected, understood, nurtured or developed.

In My Blood It Runs is working with Children’s Ground, NIYEC and a new coalition of First Nations educators from the Northern Territory to kick start his system.

What is happening with youth detention and the royal commission in the Northern Territory?

At the time of filming and release, in the Northern Territory, 100% of young people in detention were Aboriginal children.

Due to reports of abuse against inmates, a Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory was undertaken. It found:

- Detainees were frequently subjected to verbal abuse and racist remarks

- At times, some youth justice officers dared detainees, or offered bribes to detainees to carry out acts of physical violence, degrading, humiliating and/or harmful acts on each other

- The Commission finds that children were restrained by using force to their head and neck areas, including putting them in chokeholds

- ‘Ground stabilising’ children and young people by throwing them forcefully onto the ground occurred between 2010 and 2016 at the Don Dale Youth Detention Centre.

- The youth detention centres used during the relevant period were not fit for accommodating, let alone rehabilitating, children. The inadequate facilities put children and young people’s health, safety and wellbeing at serious risk.

- At times, youth justice officers deliberately withheld detainees’ access to basic human needs such as water, food and the use of toilets. This conduct was inconsistent with the basic human right contained in Article 37(c) of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child that a child treated with humanity and respect for the inherent dignity of the human person, as well as the specific rights contained in the United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty

- The practice of applying a restraint and then forcing into a prone restraint position for an extended period of time whilst a child or young person is struggling is potentially dangerous and may breach the law. This practice is also contrary to the human rights standards in Article 64 of the United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of Their Liberty

- CS gas was used on 21 August 2014 on children in circumstances where there were no guidelines, legislative or policy safeguards, specific to youth detention, which regulated its use and no research results available as to the lethal contamination time in relation to children.

- The practice of requiring all detainees who had received a family visit to be randomly subject to an unclothed search may not have complied with section 161 of the Youth Justice Act (NT), which required the Superintendent to form a belief on reasonable grounds in respect of each individual detainee.

- Isolation of children and young people was used on some detainees excessively, punitively and in breach of section 153(5) of the Youth Justice Act (NT)

- Senior executives and senior management responsible for youth detention during the latter part of the relevant period showed a disregard for the compliance with the legislation in placing children and young people in isolation for extended periods, including beyond the statutory limits in section 153(5) of the Youth Justice Act (NT)

- Senior executives and the management and staff at the detention centres implemented and/or maintained and/or tolerated a detention system seemingly intent on ‘breaking’ rather than ‘rehabilitating’ the children and young people in their care, particularly those with difficult and complex behaviours, contrary general principles contained in section 4(b) and 4(n) of the Youth Justice Act (NT), and the obligations imposed on management by sections 151(2) and 151(3)(a) and (b) of the Youth Justice Act (NT). In doing so they caused suffering to many children and young people and, very likely, in some cases, lasting psychological damage to those who not only needed their help but whom the state had committed to help by enacting rehabilitative provisions in the Youth Justice Act (NT).

Two of more than 230 recommendations included the closure of Don Dale Detention Centre, which remains open today. And raising the age of criminal responsibility in Australia (nationwide) from ten years old.

It is nearly 30 years since Australia ratified the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child. Yet we still do not have a national strategy or measures to ensure the implementation of appropriate protection of children’s rights.

I was shocked that we lock up children as young as ten years old in Australia? What is happening with the Raise The Age Campaign?

As Dujuan said at the United Nations, “I want adults to stop cruelling 10 year olds in jail”

In Australia, children as young as 10 years old can be taken out of school and away from their families, and sent to prison. All the evidence tells us that prisons traumatise children and they don’t work. Kids who spend time in prison are more likely to get in further trouble with the criminal justice system – not less.

Right now, Attorney Generals are considering whether or not to raise the age of criminal responsibility to 14 — that would mean 10 year old kids could no longer be sent to prison.

But, with many politicians believing only a ‘tough on crime’ approach wins votes, we need to convince them that they have the public support to show leadership and #RaiseTheAge.

First Nations communities have the solutions. Instead of locking kids up, we should be prioritising community-led and culturally-safe prevention, early intervention and diversionary programs that keep kids safe and families together.

Sign a petition to #RaiseTheAge here: https://inmyblooditruns.com/takeaction/#whatcanido

Where can I learn about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander truer histories?

There are a wealth of films, books, songs, essays and literature produced by First Nations people that speak to history, both across the continent and within specific nations. Most libraries have really good collections (if they don’t you should ask them to order more books by First Nations writers) and there is a range of fantastic material available online. Here are just a few suggestions to get started:

- IndigenousX

- Dark Emu – Bruce Pascoe

- The Koori History Website

- Indigenous Australia; What they don’t teach you – 3 part series from Amy McQuire

- The First Australians TV Series

- 88 Documentary Film

How can I support campaigns led by First Nations People?

- Children’s Ground

- National Indigenous Youth Education Coalition

- Stronger Smarter Institute

- Akeyulerre Healing Centre

- Warriors for Aboriginal Resistance

- Seedmob

- Reconciliation Australia

Can I screen the film in my school?

We would love you to show the film at your school! Find out how to make that happen and check out our classroom and professional learning resources here; https://inmyblooditruns.com/education/

How can I support / What can I do?

Go to our take action page for information on ways to support the family’s solutions.

- Donate to a school being established on Dujuan’s homeland at Sandy Bore supported by Children’s Ground.

- Sign a petition to #RaiseTheAge of criminal responsibility from 10 years old to (at least) 14.

- Host a screening of the film to your workplace, school or friends.

- Get your schools or your kids’ school to screen the film and download our education materials for your school.

- Host a ‘Watch Party’ of the film in your home or workplace

Beyond the impact goals specific to this film we encourage you to educate yourself, to connect with First Nations communities and to take action in solidarity with campaigns led by First Nations people. More advice on how to do that in following answers.